Reflections on Women in Social justice and Nonviolent Movements in Pakistan

Sindhiyani Tehreek activists marching as part of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD), an left-leaning political alliance formed in the late ‘80s against the military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq. Image: Sarmad Palijo via twitter

Author: Rehana Wagha

A large body of literature since the formation of Pakistan in 1947 shows that women’s struggles against patriarchy or dictatorship have remained largely nonviolent. However, there are a few notable exceptions to this statement. For example, the Mohajir Qaumi Movement of 1980s in Sindh Province and the armed conflict in Swat region post 9/11, where women were seen to be supporting violent extremism and jihadist ideology.

Different stages of the women’s rights movement

The origin and challenges of the women’s rights movement in Pakistan lie within the Islamization of both state and society. In the beginning, women who participated in the independence movement took up the task of women’s empowerment through social welfare programs aimed at women’s economic empowerment and creation of spaces promoting women’s political participation. Thus, ‘all women’ forums like the All Pakistan Women Association (APWA) were formed. This era can be coined the first phase of the women’s rights movement in Pakistan, which was mostly apolitical. Civil society organizations (CSOs) during this period operated within the given patriarchal structures without posing any challenge to the wider political state and society.

The women’s rights movement took an important turn when General Zia-ul-Haq started the Islamization of Pakistani society by imposing Martial Law in the country in 1977. It started with a campaign of a small number of urban progressive women’s rights activists of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) campaigning against the agenda of Islamization that aimed at framing the Sharia laws to control women’s bodies, promote rigid gender segregation in public spaces and strengthen patriarchal social institutions. Over time, this state policy of Islamization transformed itself decades later into the threat of Talibanization in certain parts of the North-Western frontier region of Pakistan, especially post 2001 following the 9/11 attacks.

The women’s movement in Pakistan in its early phase did not take the shape and momentum that could have led to greater social transformation and gender equality. The process of social transformation was hampered by the successive military regimes that imposed the Deobandi version of Islam, by using the scriptural interpretations of Shariah to provide legitimacy to their undemocratic actions and plans. Gen. Zia ul Haq tried to forcibly mould society into a perceived way of life attributed to an imaginary sociology of the Muslims of the past.

Given that separation between the sexes and marginalization of women—features of many older societies—became more and more impractical as time progressed, the WAF-led movement acquired greater attention among the urban middle class. With the return of democracy along with the emergence of certain donor-supported CSOs in the next decades, the women’s movement subsumed under the institutional web of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Shirkat Gah and Aurat Foundation, to name a few. Women at the forefront of resistance movement of 1980s were those who enjoyed the privileges of education, class, and urban location. The transformation started with an affordable agenda of peaceful resistance, mostly acceptable to the accompanying men of the progressive group of activists. Further, many renowned feminists seen as champions in the struggle for democracy, secularism and social justice in that period established their own NGOs which, in turn, fostered the de-politicization of the women’s right movement.

An aggressively promoted stance by opponents of secular women’s rights activists suggests that ‘feminism’ is a North American or European agenda, sometimes even speculated to be an outright conspiracy, and its local ‘westernized’ proponents are, at best, out of touch with the ground reality of Pakistani women. The result is a discomfort with and lack of ownership of the ‘feminist’ label even amongst citizens actively demanding rights and opportunities for women. Today, we see right-wing women politicians and activists curiously defending the misogynistic views expressed by the PM Imran Khan from time to time, such as the statement he made declaring sexual harassment a consequence of women’s clothing.

The impact of the parallel emergence of faith-based women’s rights organizations upon which activists and politicians endeavour to locate women’s rights in the Islamic discourse is quite visible today. Afiya Shehrbano Zia (2013) observed this phenomenon during the 1980s, when several women’s research and activists’ groups embraced the idea of the strategic worth of using the religious (Islamic) framework as a tool for negotiating and advancing women’s rights.

Moving forward, the success of the third phase of the women’s rights movement can be witnessed through the increased political participation of women in the parliament and the promulgation of pro-women laws in the past decade or so. However, the implementation of such laws has remained an issue owing to the persistence of patriarchal cultural norms and lack of institutional support. A minority of women in Pakistan in power self-identify as feminists. Yet, even those who have identified as feminists since the 1980s have been inclined to differentiate between the women’s movement—even a women’s rights movement—from a feminist one. The women’s movement would include all those seeking to bring about gender equal rights and greater autonomy for women within the operative structures of state and society. Therefore, women in right-wing political parties like Jamat e Islami, Jama’t-ud-Dawa and Al-Huda also claim to be women’s rights activists striving to promote and protect women’s rights provided by Islam by sometimes subverting the Islamic rhetoric on women’s rights in their favour.

This aforementioned division within the women’s rights movement seems to be arbitrary because it does not comprehensively cover the diversity of the women’s rights struggle taking place in various contexts. For instance, the women’s struggles under the auspices of nationalist political parties which are not properly documented. Examples include SindhiaNi Tahreek during 1980, a campaign of Baloch women against illegal disappearances of Baloch nationalist political leaders and women in the Pashtun Tahfuz Movement. Other examples of women’s struggles include the ones that have mainly revolved around livelihood rights such as that of women in Anjuman-e-mazareen Pakistan, in Fisher Folk Forum or Sindhu Bachao Tarla.

The future of women’s rights movement in Pakistan

The progress and success of the women’s rights movement in Pakistan is dependent upon the recognition of the diversity of women’s struggles and the formation of cross-sectional alliances around the broader issues, which is currently observed in the fourth phase of the women’s rights movement. For that matter it becomes necessary to comment on the Aurat March or Aurat Azadi March held across major cities of Pakistan on the 8th of March since 2018. In these marches, the presence of women from diverse backgrounds and the slogans raised is evidence that the fourth phase of women’s rights movement is vibrant and impactful.

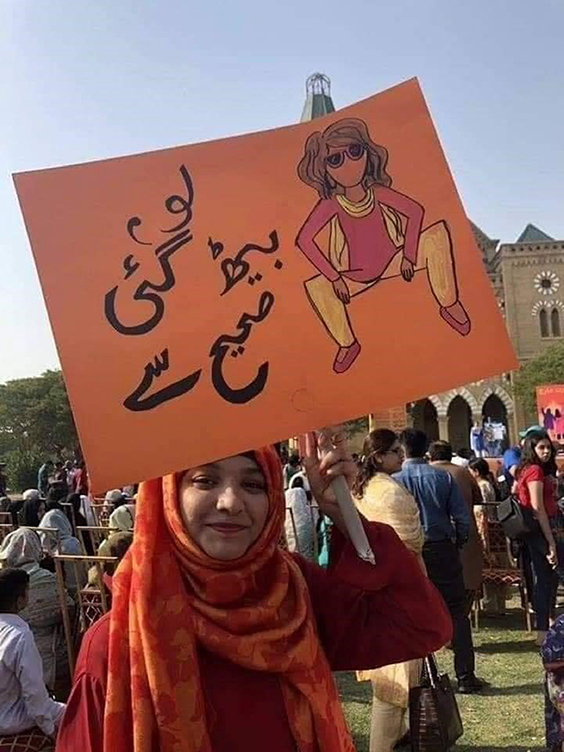

The participants of Aurat Azadi March seem to be clearer about their demands and agenda. They are not only demanding full independence and bodily autonomy in the public sphere, but also actively challenging the foundations of the private sphere. These millennial women, who voice their opinions on the internet and social media, mark a new critical juncture for feminist struggles connecting it to the transnational women’s movement by raising the slogan of ‘My Body My Right’. They are challenging the very foundations of patriarchy via the symbolic dissolution of the false gendered public and private dichotomy by holding sarcastic placards like ‘lo bethgayi sahi se’ [Look I sit appropriately].

However, the more forceful the demands of Aurat Azadi March, the stronger the backlash against the movement has been. Still, the diversity of the demands and the backlash against them, as well as the divisions and debates within the organizers and participants of the Aurat Azadi March can be termed as a part of the process which will hopefully culminate into the rise of a stronger women’s rights movement in Pakistan.

The prospects for the success of the women’s rights movement in Pakistan are inextricably tied to the participation of women activists in the broader democratic struggle and the building of alliances with pluralist political forces in the country. Moreover, the women’s rights movement will have to take into account surrounding issues of social class and ecology, which have been so far largely ignored by urban women activists, causing a disconnect and ruptures in the struggle for women’s equality and social justice.

The views and expressed in the piece above are solely those of the original author(s) and contributor(s). They do not necessarily represent the views of Centre for Social Change.

Ms. Rehana Wagha is a women rights activist. She has completed her M.Phil. in International Relations from Quaid-I-Azam University, Islamabad. Currently she is pursuing her PhD at the same university researching on women’s agency in war and conflict situations.

©2021 Centre for Social Change, Kathmandu