Nonviolent protests against marginalized groups by trade unions in Africa: Lessons from English-speaking unions in Cameroon

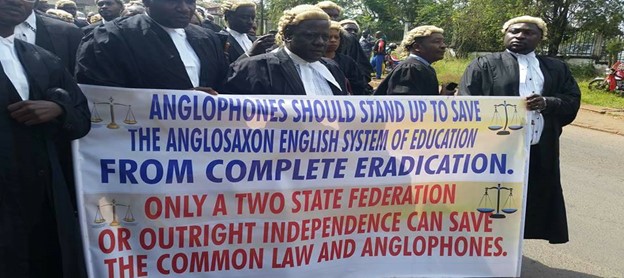

Protest marches by Common Law Lawyers in Bamenda and Limbe. Photo source: Cameroon Common Law Lawyers Association Facebook page

English-speaking unions used diverse nonviolent techniques to channel their grievances against the marginalization of the Anglo-Saxon educational and judicial sub-systems.

Author: Dr. Mengnjo Tardzenyuy Thomas

Introduction

The role of trade unions in articulating the interests of marginalized groups in any polity cannot be ignored. Cameroon is a country in Central Africa with a population estimate of 21 million inhabitants. Approximately 80 percent of this population is made up of the French-speaking community, while a minority 20 percent is the English-speaking community in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon. Trade unionism gained prominence in Cameroon during the democratization process in the early 1990s, which set the pace for the creation of associations and political parties. The peculiarity with trade unions during this epoch is that they were created and articulated on linguistic and ethnic interests. The English- speaking teachers and Common Law Lawyers were formed during this era. These unions have remained a force to reckon with in the promotion and preservation of the Anglo-Saxon education and Common Law, in the French styled dominated administration in Cameroon. This was demonstrated in the nonviolent protests led by these unions in the North West and South West Regions of Cameroon in 2016. This crisis owes its genesis to the claims which were made by these unions in relation to their respective domains to the Cameroon government through diverse nonviolent protests as examined below.

Unique features of the nonviolent protests by English speaking unions

The nonviolent protests organized by English-speaking unions in November 2016 were based on the politics of marginalized people of Anglo-Saxon origin in the educational and judicial domain. In the judicial sector, Common Law Lawyers demanded for the following: the creation of the common law department at the Advanced School of Magistracy and Administration; the re-deployment of civil law magistrates from the two common law jurisdictions; the translation of the purely French publicized Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA) into English; the creation of a law school; and the common law bench at the Supreme Court.

In the educational domain, the grievances and demands of English-speaking teachers’ unions were as follows: that qualified Anglophones were marginalized in entrance examinations to professional schools of their choices; that Francophones outnumbered Anglophones in the professional schools in Anglophone universities of Buea and Bamenda, whereas there were no Anglophones in these schools in Francophone universities; that Anglophones who applied to read medicine were usually sent to Francophone universities; that government-trained Anglophones technical teachers were trained and sent to work in Francophone areas; that francophones who lacked mastery of the English language were often sent to Anglophone schools; that the universities of Buea and Bamenda had been ‘francophonised’; that Anglophones were compelled to write some French related examinations with poorly translated questions; that lay private and confessional schools received little or no subvention from government; that the election and appointment of authorities of the Anglo-Saxon universities of Bamenda and Buea should be in strict compliance of Anglo-Saxon norms.

Nonviolent protest approaches adopted by English-speaking unions

English-speaking unions used diverse nonviolent techniques to channel their grievances against the marginalization of the Anglo-Saxon educational and judicial sub-systems. These strategies ranged from writing of petitions to the President of Cameroon in denunciation of what they considered as the “francophonisation” of the Anglo-Saxon educational and judicial system; organization of strike actions via court session and school boycotts; peaceful street demonstrations; coalition formation via the establishment of the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSA) to collectively articulate their interest; civil disobediences through ghost towns and boycotts of national events (Cameroon Civil Society Anglophone Consortium, Press Release Number 12, 9th January 2017); and to public campaigns through media outlets, such as television, radio, newspapers and social media to propagate their grievances. Worth noting is the fact that unlike previous protests, this protest by the unions demanded for a return to a federal system of government as the only panacea to permanently solve the marginalization of the English-speaking in Cameroon.

The outcome of the nonviolent protests

Most of the claims made by the unions were resolved by the government through an Ad Hoc Inter-Ministerial Committee that was institutionalized in December 2016. In the educational sector, 1000 bilingual teachers were recruited into technical schools, a state subvention of 2 billion CFA Franc was given to private schools, some French-speaking teachers were redeployed from Anglophone regions, the National Polytechnic Institute and the Department of French Private Law were created in the University of Bamenda. In the judiciary, the following measures were announced and implemented as from March 30th 2017: the OHADA Law was translated into the English Language, the Common Law bench was created at the Supreme Court, English-speaking teachers were recruited at ENAM, special recruitment of pupil judicial and legal officers as well as court registrars into ENAM is ongoing, the Common Law Department was created in Francophone universities, Anglophone lawyers were given provisional authorization to act as notaries in the North West and South West Regions and the National Commission for Bilingualism and Multiculturalism was created in January 2017.

The main lesson drawn from this is that adopting nonviolent strategies to express grievances is very significant. It is free from all forms of destructive outcomes that go along with violent protests such as destruction of properties, torture, and loss of human life.

The graphics, views and opinions expressed in the piece above are solely those of the original author(s) and contributor(s). They do not necessarily represent the views of Centre for Social Change.

Dr. Mengnjo Tardzenyuy Thomas is an Assistant Lecturer and Researcher in Public Administration and Policy in the Faculty of Law and Political Science of the University of Bamenda, Cameroon-Africa. His research interest focuses on: Mobility Policies in Africa, Decentralisation and development, Identity Crisis/Conflict, Online Political Communication and Humanitarian Policies. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Dschang, Cameroon.

©2021 Centre for Social Change, Kathmandu