From Social Media onto the Streets: How Enough is Enough Forced Nepal Government to Rethink the Pandemic

Protesters demand government improve coronavirus test services and quarantine facilities, in Kathmandu, on Saturday, June 13, 2020. Image by: Online Khabar

Author: Sarthak Bhattarai

With the COVID-19 pandemic in full swing and the Government of Nepal unable to effectively manage the crisis, Enough is Enough was initiated in early June 2020 by a group of active youngsters who insisted it remain a faceless and nonviolent citizen-movement with clear demands at its core. The campaign served as a rallying point for a huge segment of the urban youth population to demand better action, and accountability.

During the demonstration at Baluwatar, outside the Prime Minister’s residence on 31st of July in 2020, the Enough is Enough campaign transformed from what was expected to be a collective of only 15-20 people, into a movement of the masses. How this attempt at influencing and demanding better action from the government became synonymous with street activism and dissent across Nepali national media is a telling story in itself. And the unique set of strategies the campaign adopted might provide a roadmap for future civil-resistance movements in Nepal and South Asia at large.

Adopting Nonviolent Strategies

The campaign can be placed alongside other citizen-engagement efforts in Nepal such as those initiated by the Bibeksheel Party, and later Dr. Govinda KC. There were no violent mobs surging across streets, no targeted violence. No tires burned and no railings were broken.

Even while pointing out and protesting the laxity and mismanagement of the pandemic by the Government of Nepal, the campaign strategy remained nonviolent. The campaign did not introduce tall ideas but rather tied its demands to scientific facts, and demanded government efforts to adhere to the same.

The team members worked to research and compile credible resources. The campaign also found support amongst local politicians who, in their own capacity, were prompting better action, and from the international community of medical doctors, and public health experts relaying both data and tested ideas. Many among the organizers went so far as to sit on hunger strikes (Satyagraha), which invigorated and refocused the campaign, and brought an even larger public support.

The demands put forward by the Enough is Enough campaigners were fairly simple. They asked for an improved quarantine management and that the state follow the policy of mandatory PCR Testing for all vulnerable groups as defined, limiting the use of RDT to WHO recommended purposes like mass testing, or seroprevalence studies.

Initial delegations to the Ministry of Health even sought to work with the then Health Minister Bhanu Bhakta Dhakal, but quickly realized that the government authorities were either dismissive, or worse defensive about the reckless management of the pandemic. It was at this point that the team realized the need for a far more massive call-to-action and protest en masse. The organizers say even street activism was never thought of as the primary form of protest.

From Social Media to the Streets

Enough is Enough also proved strategically shrewd in its use of social media. Expanding from a personal following of the initial team, word spread even further as Nepali celebrities started sharing the campaign’s posts and stories on Facebook and Instagram. The movement went viral and within a few days and the Enough is Enough Facebook Group had over 200 thousand members from across the country. Thereon, it did not take long for the numbers to spill onto the streets. Tied with public frustration towards the government, youth across the country, particularly in Kathmandu joined the protests. This coincided with the news of large corruption scandals in procuring medical equipment within the ministry.

As the demands for accountability started to overshadow the initial demand for better pandemic management, the campaign inevitably turned political. Government authorities, particularly the ruling political faction, took no time in naming the campaign a political stunt as opposition party members started to visit the Satyagrahis, pledging moral support. Even the Satyagrahis came under fire as being politically influenced and the campaigners were condemned as being ‘elitist’. However, relentless support from the public and professionals alike saw the cause prevail and the government had to come to terms with the campaign’s demands.

Impact and Lessons

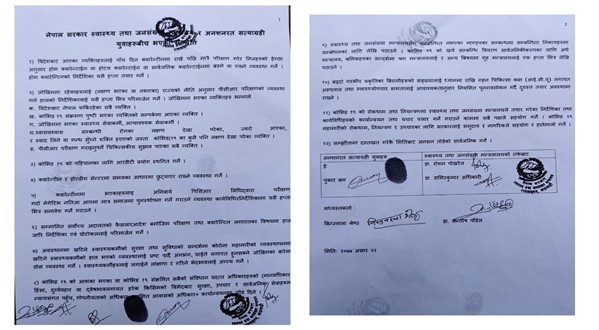

Enough is Enough stood unique in its successes that expanded beyond the signing of the twin agreements which prompted policy shifts in the COVID-19 testing and management of quarantine centers, including the discontinuation of use of RDT at quarantine centers as primary testing and later with the government mandating PCR testing as the primary diagnostic method.

Not only did it tackle the cognitive dissonance of where and how movements should begin, the Enough is Enough campaign managed to rouse the usually politically inactive urban youth to collectively dissent. Furthermore, the strategic dissemination of public health information contributed towards improving literacy on health and policy.

Enough is Enough has defined a “new normal” in nonviolent political action– where affirming human rights and demands for improved government action are not in the purview of just the opposition, or the oppressed and marginalized, but of everyone.

Viral social media posts and extensive media coverage of the campaign both hold important lessons for similar campaigns. Almost all Nepali national media, including smaller online portals widely covered the hunger strikes, demonstrations, and consequent government reprisal.

Similarly, interviews with public health professionals who slammed the half-hearted measures of the government proved helpful in rallying the people for the campaign’s cause. Consequently, even as fear of the virus was at its peak, through smart-phones, and smart-strategies, a new form of nonviolent resistance emerged.

Enough is Enough has shown the importance of campaigning on all fronts. Aalok Subedi, one the initial members of the campaign, observes how this campaign demonstrated that the streets (Sadak), the Parliament (Sadan) and the court (Adalat) could all be battlegrounds for citizen-led movements. He also makes a note of how the many Public Interest Litigations (PILs) filed at court helped to further the campaign cause.

Today, according to organizers, the campaign continues to maintain the form of a faceless movement, and provides a platform for knowledge building, prompting changes to control measures for the pandemic. Volunteers contribute by researching and putting out new verified medical information on Twitter and Facebook. While it might be an overstatement to pronounce Enough is Enough a precursor to such, but many a movement, like the #RageAgainstRape and Women’s March among others continue to see a large turnout of urban youth in continuation of the collective consciousness towards change.

The views and opinions expressed in the piece above are solely those of the original author(s) and contributor(s). They do not necessarily represent the views of Centre for Social Change.

Mr. Sarthak Bhattarai is a student of Social Work at Tribhuvan University, Nepal. He is involved as a research intern in ‘Governance Monitoring Centre Nepal (GMC Nepal)’ project at Centre for Social Change (CSC), Kathmandu.

©2021 Centre for Social Change, Kathmandu